An experiment run in 1979 by Prof. Alexander Schauss tested the ability of the mere presence of a color to affect actual physical strength in humans. Half the men in the experiment stared at a deep blue color for one minute. The other half stared at the color pink. After the minute, participants were asked to perform strength tests, such as lifting their arms against a counter-force and squeezing a device called a dynamometer. Overwhelmingly, participants recorded a significant decrease in physical strength when asked to stare at the color pink. After the experiment was published as a scientific paper, light bulbs went off across the country. Holding cells at the U.S. Naval Correctional center in Seattle were painted pink, as were several detention centers. All reported a significant decrease in aggressive behavior. Doctors, teachers, parents and (you guessed it) jails with “drunk-tanks” began to try shades of pink in attempts to calm people down. Football coaches even began to paint their visitors’ locker-rooms pink to gain the upper hand. (Several conferences later outlawed this practice, but perhaps not before it sapped the strength of a few mighty foes?)

Many of the color choices we make every day — what to wear, what to paint a room — are made almost entirely without conscious thought. A designer, however, cannot ignore these hidden meanings. To affect people emotionally, to make them pay attention and care about the message, you have to use every tool in the toolbox.

The story of this experiment is found in Adam Alter’s Drunk Tank Pink (and other forces that shape how we think, feel, and behave). It’s a great read, easy to consume in fascinating bite-sized chunks. Alter jumps from experiment to experiment to uncover these hidden forces, and many of them just make you shake your head in disbelief at the predictable unpredictability of the human race. Here are a few facts to whet your appetite:

We are much more likely to donate money if the name of the organization or cause shares alphabetical letters found in our own names.

What? Really? Because my name is Kyle, I am more likely to contribute to a Katrina disaster-relief fund than one for Hurricane Rita? The answer is “yes,” people feel a subconscious magnetic attraction and preference for characters in the alphabet found in their own names.

This disaster has my name all over it.

This disaster has my name all over it.

The color red could make you more attractive.

Alter recounts an experiment in the world of online dating to observe the effects of color in the all-important profile picture. Participants used a single profile image, but the color of their clothing was digitally altered every two weeks. During a nine-month period, the color changed from red to black to white to yellow to blue to green. The period during which the red shirt was displayed brought in 21% of all inquiries, even though it was only displayed about 12% of the time. Now if you’ll excuse me, I gotta go change my shirt.

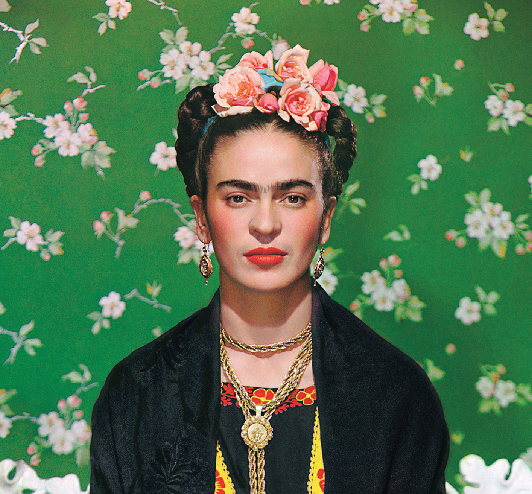

This do anything for ya? How ‘bout now?

This do anything for ya? How ‘bout now?

Disfluent typography gets your guard up.

Fluent typography can be defined as user-friendly. Legible typefaces like Helvetica are widely utilized to communicate as clearly as possible. The author says humans have a tendency to act like “cognitive misers” when exposed to fluency, meaning we devote as few mental resources as possible to absorb the information in front of us. The opposite experience, disfluency, can affect us in a couple of interesting ways. A typeface or color palette that skews disfluent can act as a signal that more mental resources are needed for comprehension. In the book, Alter describes some tricky logic questions that evoke immediate and incorrect responses. When the same question was written is a less fluent typeface, test-takers got the answer right more often. Visual disfluency has also been proven to decrease an audiences desire to share personal information online, and can affect your own scale of right and wrong, positive and negative. Look at the example below. Do you think the fluency or disfluency of presentation might affect how you would rate the moral wrong-ness of this act on a scale of 1-10? Read the book to find out.